A critical system of ocean currents could collapse much sooner than expected as a result of the deepening climate emergency, according to the findings of a new study, potentially wreaking havoc across the globe.

Peer-reviewed analysis published Tuesday in Nature Communications estimated that the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), of which the Gulf Stream is a part, could collapse around the middle of the century — or even as early as 2025.

Climate scientists who were not involved in the study acknowledged that the current has become less stable, but urged some caution in parsing the findings of the research.

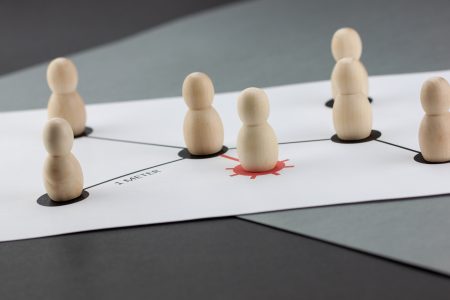

The AMOC acts like a conveyor belt of currents carrying warm waters from north to south and back in a long and relatively slow cycle within the Atlantic Ocean. The circulation also carries nutrients necessary to sustain ocean life.

A better known section of this circulation is the Gulf Stream, a wind-driven current that keeps major parts of Europe and the east coast of Florida warm, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

For one, the NOAA says England would have a “much colder climate” if not for the warm waters of the Gulf Stream.

The projected collapse of the AMOC is seen as a “major concern” because it is recognized as one of the most important tipping elements in the Earth’s climate system.

The study tapped on sea surface temperature data from 1870 as a proxy for changes in the Gulf Stream’s currents across the years, before extrapolating the data to estimate when a tipping point could take place.

Scientists have previously sounded the alarm over studies showing a rapid slowdown of the AMOC.

That being said, the U.N.’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change assesses that the Gulf Stream is not likely to collapse this century, expecting the current to “weaken but not cease.”

‘A collapse of the AMOC would be disastrous’

“This study highlights that the North Atlantic circulation is showing signs of instability, which might indicate that a collapse of the overturning could occur, with major climate implications,” said Andrew Watson, professor at the University of Exeter.

“The instability could also be less dramatic, not a full-scale shutdown but a change in the sites of deep water formation,” he added.

Another professor is of the view that the Gulf Stream has been losing stability, but disagreed with the study’s outcome, saying that the uncertainties are “too high” to reliably forecast a time of tipping.

“The uncertainties in the heavily oversimplified model assumptions by the authors are too high,” said Niklas Boers, professor of Earth system modelling at the Technical University of Munich.

Regardless, a close evaluation of the current is still a priority.

“A collapse of the AMOC would be disastrous,” said Jonathan Bamber, director of the Bristol Glaciology Centre at the University of Bristol.

“This study highlights how important it is to continue to monitor AMOC variability and to improve our understanding of its stability under present-day and future climate conditions.”

Read the full article here