Humans like choice. Indeed, it’s a bedrock principle of autonomy and freedom.

But when it comes to investing, having too many choices can be bad.

“Most likely, it will hurt you rather than help you,” said Philip Chao, a certified financial planner and founder of Experiential Wealth, based in Cabin John, Maryland.

The dominant view in economics is that more options are “unambiguously” good.

To that point, a “rich” environment of choice lets consumers “curate an experience tailored to their preferences,” wrote Brian Scholl, chief economist of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission Office of the Investor Advocate.

However, in the real world, our experience diverges from this paradigm, he said.

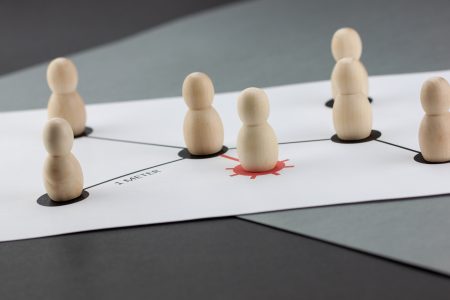

Humans get overwhelmed by too many options, a behavioral finance concept known as “choice overload.”

Often, people — especially those new to something that carries high stakes — are fearful of making a bad choice or regretting their decision, said CFP David Blanchett, head of retirement research for PGIM, an investment manager.

This paradox of choice can have many negative impacts on investors: inertia, or doing nothing; naïve diversification, or spreading money across a little bit of everything; and favoring attention-grabbing investments, wrote Samantha Lamas, senior behavioral researcher at Morningstar.

“These shortcuts can become disastrous mistakes,” she said.

How investors encounter choice overload

It’s not just investing: The choice paradox can extend to things like ice cream flavors and apparel, for example.

Among the early research experiments: buying gourmet jam at an upscale grocery store. According to that 2000 study, by Sheena Iyengar and Mark Lepper, a tasting booth with a large display of exotic jams (24 varieties) received more customer interest than a smaller one with six varieties. But customers who saw the small display were 10 times more likely to buy jam than those who saw the larger one.

Given these behavioral biases, retailers and others have evolved, making it less likely consumers will experience choice overload “in the wild” today, said Dan Egan, vice president of behavioral finance and investing at Betterment.

More from Personal Finance:

A 12% retirement return assumption is ‘absolutely nuts’

Why the ‘last mile’ of the inflation fight may be tough

Don’t let this passport quirk upend your next vacation

However, let’s say an investor wants to save money in a taxable brokerage account or individual retirement account. They generally have hundreds or even thousands of options available from which to choose, and several characteristics to compare, such as cost and performance.

“There’s literally more choice than would ever be useful to you,” Egan said.

It’s a bit different in the context of 401(k) plans, experts said.

Do-it-yourselfers may have about one to two dozen investment options, at most, from which to choose, reducing the choice friction.

Further, most employers automatically enroll workers into a target-date fund, a one-stop shop for retirement savers that’s generally well diversified and appropriately allocated based on the investor’s age. This eliminates much of the decision-making.

If you don’t give people an easy choice, “it’s really hard for them,” Blanchett said.

Make it as simple as possible

Ultimately, long-term investors who are paralyzed by their available choices should make the process as simple as possible when starting out, experts said.

For most people, that’s likely to be investing in a well-diversified mutual fund like a target-date fund or a 60/40 balanced fund (which is allocated 60% to stocks and 40% to bonds), experts said.

“Either one of those [funds] is an excellent place to start as opposed to putting all money in cash or not investing,” Blanchett said.

Even within TDFs and balanced fund categories, there can be dozens of different options. Experts recommend seeking out a provider like Vanguard Group with relatively low costs. (You can do this by comparing the “expense ratios” of various funds.)

Here’s another approach: If you open a brokerage account at Vanguard, Fidelity or Charles Schwab, for example, use their respective TDFs or balanced portfolios, Blanchett said. In these cases, you’re offloading most of the investment decision-making to professional asset managers, and the large providers generally have high quality, he said.

“Is it necessary to buy all the ingredients to make a cake, or can you just buy a cake and eat it?” Chao said.

Don’t miss these stories from CNBC PRO:

Read the full article here