For three days in early 2012, as a hotly contested presidential primary consumed the Republican Party, the Conservative Political Action Conference basked in the spotlight.

Thousands of conservative die-hards and hundreds of reporters descended on Washington that February for the annual gathering of the political right. The lineup that year not only featured marquee speeches from the leading remaining presidential hopefuls, Mitt Romney and Rick Santorum; it also offered a venue for that cycle’s unsuccessful candidates to take a bow before the GOP base and for some rising Republican stars to test the waters for 2016.

But at this year’s CPAC, which began Wednesday amid the throes of a presidential race once more, there’s little space in the agenda for 2024 also-rans or to showcase the party’s future. Nor is there a spot for former South Carolina Gov. Nikki Haley, who is still competing for the GOP nomination. Instead, it’s a four-day fete with one man at the center: Donald Trump.

The roster of speakers includes MAGA influencers, right-wing conservative media personalities who regularly flatter the former president and people who served in Trump’s administration. Trump himself will address the conference Saturday before heading to South Carolina to watch the results come in for the state’s GOP primary.

Yet despite the event landing on the same day as the South Carolina primary this year, the former president is expected to use the CPAC stage to focus on contrasting his record with that of President Joe Biden in a preview of a likely general election matchup, a Trump adviser told CNN.

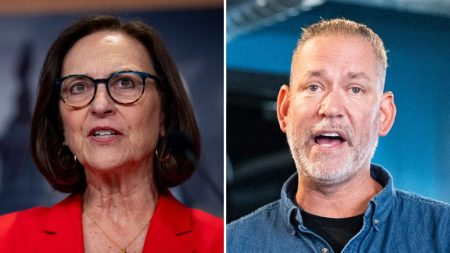

This year’s Trump-centric CPAC will also serve as the unofficial kickoff to the GOP vice presidential stakes. Some of the most talked-about potential running mates will address the CPAC audience in what can only be described as an audition of sorts to test how they are received by the Trump faithful.

Among the contenders scheduled to speak are New York Rep. Elise Stefanik, the No. 4 House Republican; entrepreneur and recent presidential candidate Vivek Ramaswamy; Ohio Sen. JD Vance; Trump’s former Housing and Urban Development secretary, Ben Carson; Florida Rep. Byron Donalds; former Democratic Rep. Tulsi Gabbard of Hawaii; South Dakota Gov. Kristi Noem; and Arizona Senate candidate Kari Lake.

Multiple people close to the former president argue that while Trump has a habit of floating names to allies and donors to take their temperature on potential ticket mates, he is far from a decision.

Another source said that Trump has told senior advisers he doesn’t want to get ahead of the primary process by vetting a potential running mate too early, indicating it was bad luck. However, his advisers also acknowledge that the jockeying for the job has clearly begun.

CPAC attendees will vote on their favorites to join Trump on the ticket this November in the conference’s straw poll.

Trump himself has fueled the speculation. Asked by Fox News host Laura Ingraham on Tuesday if Ramaswamy, Donalds, Noem and Gabbard were on his short list, along with South Carolina Sen. Tim Scott and Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, the former president replied: “They are.”

“Honestly, all of those people are good,” he said. “They’re all good. They’re all solid.”

Being a potential vice presidential pick for Trump means having to walk a fine line, with CPAC being one such test. Prospective running mates must both brandish their conservative credentials and extensive loyalty to Trump, while also not looking overly eager to join him on the 2024 ticket, a person close to the former president cautioned. They must be interesting, good messengers and popular, but not in a way that may upstage Trump. That risk was evident in one recent episode when Trump privately complained about an ally he shared a stage with for “talking too much,” only to call on the person to speak at a later event, two sources close to the former president told CNN.

Started in 1974, CPAC became a space for conservatives to engage in policy debate and for the grassroots to make themselves heard by the party’s Washington insiders. Candidates and party leaders have made the sojourn to CPAC year after year to take the temperature of the base and test their standing with the thousands of conservatives packed into hotel ballrooms.

Trump’s relationship with CPAC began in 2011 when he was still a businessman and reality television star flirting with presidential politics. Like many Republican hopefuls before him, Trump appeared at the annual confab to convince the crowd of his conservative bona fides.

“I’m pro-life. I’m against gun control,” he told attendees. “And I will fight to end Obamacare and replace it.”

But like the rest of the Republican Party, CPAC became an extension of Trump’s political operation after he took office. Speaking at the conference in 2017 shortly after Trump’s swearing in, presidential adviser Kellyanne Conway quipped that the conference would soon become “TPAC.” The rebranding lasted through Trump’s term as president and has stuck even in the years since he left office.

“I don’t recognize it anymore,” said Al Cárdenas, a former chairman of the American Conservative Union, which holds the event. “It all gravitates around Donald Trump.”

Trump allies have pushed back on the notion that the event has changed or is potentially less significant, saying it is indicative of the change in a party that has continued to coalesce around Trump.

Some Republican presidential hopefuls have in recent years dared to make a play for the CPAC faithful. None have succeeded.

DeSantis tossed hats and received a hero’s entrance from a friendly crowd at the 2022 gathering in Florida but still handily lost the event’s famed straw poll to Trump. Haley urged CPAC attendees last year to “put your trust in a new generation,” and in response Trump supporters heckled her in the hallways. Former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, another Trump administration alumnus who considered a 2024 bid, similarly tried to drive a wedge between CPAC and the former president in his remarks there in 2023; he never made it to the starting line of the GOP presidential race.

None of those individuals are speaking at this week’s gathering. Among Trump’s 2024 rivals, only Ramaswamy – who praised Trump even as he ran against him – will speak at CPAC. He will deliver the keynote address at Friday’s dinner. Contrast that with 2012, when unsuccessful presidential candidates, including Minnesota Rep. Michele Bachmann, Texas Gov. Rick Perry and businessman Herman Cain, each received a turn at the mic.

That year, CPAC also exhibited the GOP’s ascending figures. Florida Sen. Marco Rubio opened the conference, and former Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker earned raucous applause during his remarks. Both would go on to run for president in 2016.

This week, though, for the second straight year, many of the party’s rising members of Congress and governors are avoiding the conference. Nor will the event feature party leaders in Washington. The former president’s top allies on Capitol Hill – such as Reps. Matt Gaetz and Jim Jordan – will address the confab but not Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell nor House Speaker Mike Johnson.

Some Republican operatives say the lack of interest is reflective of a CPAC diminished by both its fealty to Trump as well as the controversies that have swirled around the conference’s leadership in recent years. American Conservative Union Chairman Matt Schlapp last year faced multiple allegations of sexual assault, including from a GOP political strategist who accused Schlapp in a lawsuit of groping and fondling his groin during a car ride. Schlapp denied wrongdoing at the time through an attorney. Shortly after the allegations first came to light, Trump and Schlapp appeared together at a CPAC fundraiser at the former president’s Mar-a-Lago home in Florida.

Amid the turmoil, CPAC also experienced turnover on its board.

Attempts to reach Schlapp by phone before CPAC were unsuccessful.

David Kochel, a GOP strategist for Romney during the 2012 campaign against Santorum, said Republicans once treated CPAC as a meaningful showcase for candidates. Now, he said, it’s “not a serious organization” and called it a “grift.”

“It’s the ‘Star Wars’ bar scene of performative, minor conservative celebrities based on their Twitter following and how rogue-ish they can behave,” Kochel said. “It’s a chaos platform for disrupting the so-called establishment, though, increasingly, they are the establishment.”

Read the full article here