Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Electric vehicles myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

The Biden administration is giving carmakers an extra three years to meet aggressive emissions targets, bowing to pressure from manufacturers, auto workers and the oil industry in a move that could slow the adoption of electric vehicles.

The Environmental Protection Agency on Wednesday released a final rule regulating emissions from cars and light trucks that will demand the steepest cuts to vehicle emissions starting in 2030, not from 2027 as first proposed last year.

Transport is the largest source of US carbon dioxide emissions. The EPA had called the rule “the most ambitious pollution standards ever for cars and trucks” when the proposal was floated, boosting the US’s chance of achieving pledges under the Paris climate agreement.

The rule has since been the focus of fierce lobbying from the oil and gas industry along with some carmakers. The American Fuel & Petrochemical Manufacturers, an oil refinery trade group, spent millions of dollars on advertisements in 2024 election battleground states decrying an “EPA car ban”.

Electric vehicle sales growth has slowed in the US, with potential buyers turned off by sparse charging infrastructure and the relatively high price tag compared with combustion engine cars. US carmakers including Ford, General Motors and Tesla have all recently paused plans to expand EV manufacturing capacity.

As first proposed, the rule would have in effect forced carmakers to make 67 per cent of their US models electric by 2032, up from less than 8 per cent of total sales last year. A summary of Wednesday’s final rule laid out “technology neutral” scenarios in which manufacturers can produce a diverse range of “clean” cars, including cleaner petrol cars, hybrid electric vehicles, plug-in hybrids and fully electric vehicles.

The rule comes as President Joe Biden seeks to slash US emissions and tackle climate change while also winning re-election in November. Among those concerned about a swift rollout of electric vehicles is the United Auto Workers union, which has endorsed Biden for 2024.

The manufacturing of EVs requires fewer workers than building combustion cars and trucks, threatening to shrink the number of jobs available. The UAW had warned that the EPA’s original proposal presented an “unrealistic” projection of EV adoption, and pushed for more time to build up the domestic manufacturing base.

The American Petroleum Institute, the largest US oil lobbying group, told the Financial Times this week that the EPA’s original proposal was flawed, undermined consumer choice and would have repercussions in the upcoming election.

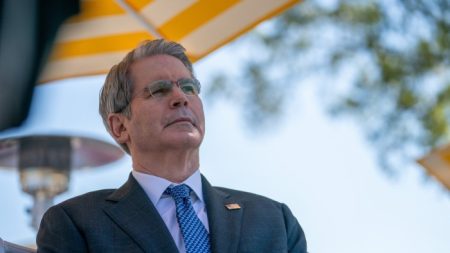

“This is a tax on people who can least afford it, people who drive long distances to get to work . . . They want to take away your gas car. I mean, I think it will be a big issue in this campaign,” said Mike Sommers, API’s chief executive.

According to InfluenceMap, a group that monitors lobbying efforts, carmakers broadly advocated for electrification targets of 40 to 50 per cent by 2030, a lower rate than the 60 per cent implied by the EPA’s original proposal.

The Alliance for Automotive Innovation, a trade group, said that carmakers were “committed to the EV transition”, but that slowing the pace of EV adoption between 2027 and 2030 was “the right call” and presented “more reasonable electrification targets”.

“The rules are mindful of the importance of choice to drivers and preserve their ability to choose the vehicle that’s right for them,” said John Bozzella, chief executive of the alliance.

The final rule is expected to avoid a cumulative 7.2bn tonnes of CO₂ emissions by 2055, roughly equal to four times the emissions of the entire transport sector in 2021, the EPA said.

“On factory floors across the nation, our autoworkers are making cars and trucks that give American drivers a choice — a way to get from point A to point B without having to fuel up at a gas station,” said Ali Zaidi, Biden’s national climate adviser. “From plug-in hybrids to fuel cells to fully electric, drivers have more choices today.”

Manish Bapna, president of the NRDC Action Fund, an environmental advocacy group, said the adjustments to the EPA’s rule “don’t represent a material change in the carbon reduction benefits” when compared with the original version.

“We need to build an unstoppable shift to cleaner cars, and that is what this rule does”, Bapna said.

Read the full article here