Japan has begun campaigning for a snap general election that threatens to pummel the ruling Liberal Democratic party as voters pass judgment on a slush-fund scandal, the rising cost of living and a decade-long failure to deliver greater household prosperity.

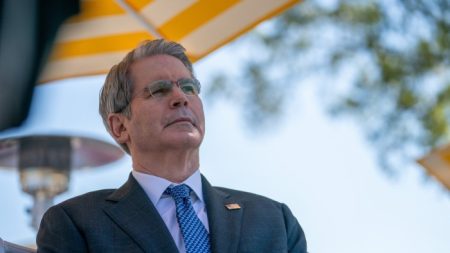

The intensive 12-day campaigning season for a vote to be held on October 27 was formally set in motion by Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba — the quirky, 67-year-old LDP veteran who was elevated to the top job two weeks ago after a bitterly divisive party leadership race.

Pitted against Ishiba is a fragmented line-up of five main opposition parties, with no strong inclination to join forces. The largest is the Constitutional Democratic party of Japan — itself a divided bloc led by the 67-year-old parliamentary veteran and former prime minister, Yoshihiko Noda.

While the LDP is still likely to secure a majority, it may emerge substantially weakened and less able to tackle the economic and demographic challenges Tokyo faces.

Japan is attempting to normalise its economy after decades of deflation and ultra-loose monetary policy, while its shrinking working population has to support an ever larger number of retirees.

Ishiba’s success may be defined by how few seats he loses at a time when the LDP is held in low esteem.

“Ishiba may be able to afford up to 20 or so losses, particularly if they are concentrated among scandal-implicated lawmakers, but more than that will impair his ability to govern,” said Tobias Harris, the founder of political risk advisory firm Japan Foresight.

Despite his image as a man of integrity, Ishiba came to power with a cabinet approval rating of 51 per cent — the lowest since that index began in 2002. In the first trading session after Ishiba emerged as Japan’s next prime minister, Tokyo stocks plunged heavily while the yen traded wildly as markets bet on whether he would press the Bank of Japan to delay interest rate increases.

That lack of market confidence hangs over Ishiba’s attempt to present himself as a revitaliser of Japan’s economy.

As Mizuho Securities strategist Masatoshi Kikuchi pointed out, while the economic backdrop of many previous elections has been poor, Japan’s long experience with falling or stagnant prices meant that the “misery index” — a calculation that adds together the unemployment rate and inflation rate — had not been much of an issue. Now, with rising prices and anaemic real wage increases, the misery index is close to 6 per cent.

Given the long shadow cast by the political funding scandal and the state of the economy, the LDP is, in theory, due to a heavy drubbing from the electorate, said Temple university political scientist Jeff Kingston.

But, he added, the speed at which the general election has been called has given the opposition parties too little time to effectively co-ordinate.

Noda, meanwhile, has so far failed to set out a distinctive economic programme or give voters a clear set of policy reasons for electing his party, repeating the mantra that Japan should vote out the long-incumbent LDP and allow Japanese politics space to change.

“There are lots of reasons why the LDP should suffer, but the fragmented state of the opposition is what could save them. I’m not sure that Noda is the man to lead the CDPJ into a bright future,” said Kingston, who added that voters had likely not forgiven the party for the brief but chaotic period it was in power from 2009 to 2012.

Still, the risks of a significant upset are there, say other analysts. Ishiba’s LDP party, in power more or less continuously since 1955 barring two short interludes, remains deeply split after its leadership election and Ishiba has done little to build unity.

The power balance in the House of Representatives, where the LDP controlled 255 of 465 seats before parliament’s dissolution, means the loss of just a couple of dozen seats would strip Ishiba of an absolute majority and give greater leverage to powerful foes within his own party.

The LDP has also, for many years, ruled in coalition with the Komeito party, which has 32 seats but is weakening, and a handful of independents. If the coalition loses more than 46 seats, noted Harris, it will fall short of the 244-seat “stable majority” that allows it to chair, and hold a majority of seats on, each parliamentary committee.

While Ishiba — a train enthusiast and Japanese anime fan obsessed with defence issues — had personal popularity, he was not the “charismatic saviour” the LDP needed, said one party official.

But Harris added that the chances were good that independent voters, especially younger ones, could reject the choice between the two 67-year-old political veterans and sit out this election. That could mean the election is decided by LDP grassroots supporters, who tend to like Ishiba and will leave the LDP’s majority intact.

“The LDP looks likely to lose votes by quite a bit, but it’s unclear how big their loss of seats would be given that more voters may simply abstain and also split votes between opposition parties,” said Koichi Nakano, a political scientist and affiliate at the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs at Harvard University.

“If there was a real two-party system . . . the LDP would be almost certain to lose power, but given the voter’s disaffection and the opposition fragmentation, the LDP may still weather the storm.”

Data visualisation by Jonathan Vincent

Read the full article here