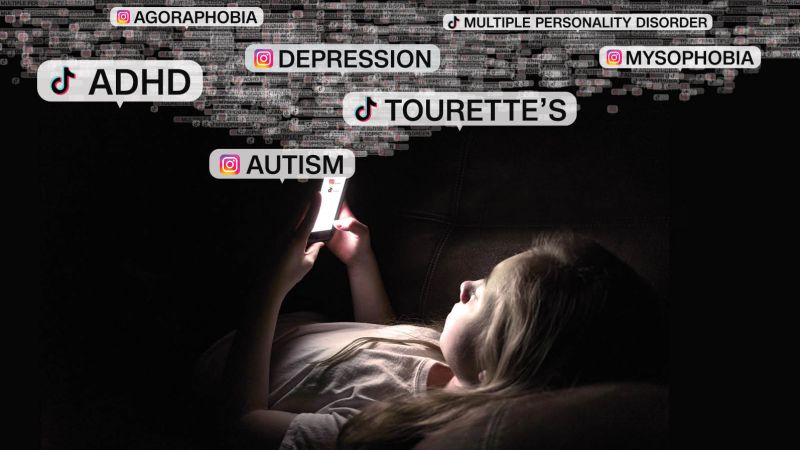

Some people browse TikTok and Instagram for recipes, memes and colorful takes on the news. Erin Coleman says her 14-year-old daughter uses these apps to search for videos about mental health diagnoses.

Over time, the teen started to self-identify with the creators, according to her mother, and became convinced she had the same diagnoses, including attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), depression, autism, mysophobia (an extreme fear of dirt and germs) and agoraphobia (a fear of leaving the house).

“Every week, she would come up with another diagnosis,” Coleman told CNN. “If she sees a hint of herself in someone, she thinks she has it, too.”

After undergoing testing for mental health and medical conditions, her daughter was diagnosed not with the long list of conditions she’d speculated about but with severe anxiety. “Even now, she doesn’t always think [the specialists] are correct,” Coleman said.

Social media platforms, including TikTok and Instagram, have come under mounting scrutiny in recent years for their potential to lead younger users to harmful content and exacerbate what experts have called a national mental health crisis among teens. But Coleman is one of nearly two dozen parents who told CNN that they are grappling with a different but related issue: teens using social media to diagnose themselves with mental health conditions.

A growing number of teens are turning to social platforms such as Instagram and TikTok for guidance, resources and support for their mental health, and to find conditions they think match their own – a trend that has alarmed parents, therapists and school counselors, according to interviews with CNN. Some teens start to follow creators who discuss their own mental health conditions, symptoms and treatments; others have come across posts with symptoms checklists to help decide if they meet the criteria for a diagnosis.

Using the internet to self-diagnose is not new, as anyone who has used WebMD knows. And there can be some benefits. Some parents said social media has helped their teens get mental health information they’ve needed and has helped them feel less alone.

However, many parents and experts expressed concerns over how self-diagnosing and mislabeling could exacerbate teens’ behaviors, make them feel isolated and be counterproductive in getting them the help they need. In a worst case scenario, teens could set themselves on a path to receiving medication for a condition they do not have. And once teens search for this mental health content, the algorithms may keep surfacing similar videos and posts.

And like Coleman, some parents and therapists have found that once teens decide they have a condition, it can be hard to convince them otherwise.

Dr. Larry D. Mitnaul, a child and adolescent psychiatrist in Wichita, Kansas, and the founder and CEO of well-being coaching company Be Well Academy, said he’s seen an alarming number of teenagers self-diagnosing from social media posts.

“Teens are coming into our office with already very strong opinions about their own self-diagnosis,” he said. “When we talk through the layers of how they came to that conclusion, it’s very often because of what they’re seeing and searching for online and most certainly through social media.”

According to Mitnaul, the most popular self-diagnoses he’s encountering among teenagers are ADHD, autism spectrum disorder and dissociative identity disorder, or multiple personality disorder. He said teens previously would come to his clinic to discuss symptoms but did not have a particular diagnosis or label in mind. He started to notice a significant shift in 2021.

“When I’m sitting down with a teen, that’s a time or window of their life where they’re experiencing a lot of different high-intensity emotions, and it can be jarring, unnerving and affect their sense of identity,” he said. “But it doesn’t necessarily mean they have a rare mood disorder that has fairly intense consequences, treatment and intervention.”

Developing an inaccurate sense of who they are from a non-professional diagnosis can be harmful. “Mislabeling often makes a teen’s world smaller when they go out and look for friend groups or the way they identify,” he said.

It can also put parents in an impossible position, and finding help isn’t always easy.

Julie Harper said her daughter was outgoing and friendly but that changed during the Covid-19 lockdown in 2020, when she was 16. Her daughter was diagnosed with depression and later improved on medication, but her moodiness escalated and new symptoms surfaced after she started to spend longer hours on TikTok, according to Harper.

“My teen is obsessed with getting an autism diagnosis,” she said. But they’ve been unable to get formal testing due to long waitlists in Kentucky. “Did TikTok help us figure some things out or send us on a wild goose chase? I still don’t know.”

Some experts believe teens may be over-identifying with a specific label or diagnosis, even if it is not a fully accurate representation of their struggles, because a diagnosis can be used as a shield or justification of behavior in social situations.

“With the mounting pressure that young people face to be socially competitive, those teens with more significant insecurities may feel that they will never measure up,” said Alexandra Hamlet, a clinical psychologist in New York City who works with teenagers. “A teen may rely on a diagnosis to lower others’ expectations of their abilities.”

Social media users posting about psychiatric disorders are also often seen as trustworthy to teens, either because they too suffer from the disorder discussed in the video or because they self-identify as experts on the topic, experts say.

According to Hamlet, social media companies should tweak algorithms to better detect when users are consuming too much content about a specific topic. A disclaimer or pop-up notice could also remind users to take a break and reflect on their consumption habits, she said.

In a statement, Liza Crenshaw, a spokesperson for Instagram parent Meta, said the company doesn’t “have specific guardrails in place outside of our Community Standards which would of course prohibit anything that promotes, encourages or glorifies things like eating disorders or self-harm.”

“But I think what we see more often on Instagram is people coming together to find community and support,” Crenshaw said.

Meta has created a number of programs, including its Well-being Creator Collective, to help educate well-being and mental health creators on how to design positive content that aims to inspire teens and support their well-being. Instagram also introduced a handful of tools to cut down on obsessive scrolling, limit late-night browsing and actively nudge teens toward different topics, if they’ve been dwelling on any type of content for too long.

TikTok did not respond to a request for comment, but it has taken steps to let users set regular screen time breaks and add safeguards that allocate a “maturity score” to videos detected as potentially containing mature or complex themes. TikTok also has a parental control feature that allows parents to filter out videos with words or hashtags to help reduce the likelihood of their teen seeing content they may not want them to see.

Still, the online self-diagnosing trend comes at a perilous moment for American teens, both online and offline.

In May, the US Surgeon General issued an advisory note that stated social media use presents “a profound risk of harm” for kids and called for increased research into its impact on youth mental health, as well as action from policymakers and technology companies.

Linden Taber, a school counselor in Chattanooga, Tennessee, said students are still reeling from the effects of a global pandemic, and many therapists and psychiatrists have months-long wait-lists – not to mention the financial inaccessibility of some of these services.

“I’ve seen an increase in psychological vocabulary among teens … and I believe this is a step in the right direction because as a society, we’ve decreased stigmatization,” she told CNN. “But we haven’t increased access to support. This leaves us, and especially teens, in a vacuum.”

She argues that when a student self-diagnoses based on information they’ve seen on the internet, it can often feel “like a sentencing … because there isn’t always a mental health professional there to walk them through the complexity of the diagnosis, dispel myths and misconceptions, or to offer hope.”

For some, however, social media has had a positive impact on connecting people with mental health information or helping them feel less alone.

Julie Fulcher from Raleigh, North Carolina, said she began following ADHD influencers who were able to better explain behaviors, impulsivities and how the condition is related to executive functioning, so she can help her daughter navigate her diagnosis.

Meanwhile, Mary Spadaro Daikos from upstate New York feels mixed about her daughter using social media for reasons related to her autism diagnosis. “She’s doing a lot of self-discovery right now in so many areas, and social media is a big part of that,” she said. “I know social media gets a bad rap, but in her case, it’s hard to tell sometimes if the pros outweigh the cons.”

Many adults appear to credit social media with helping them identify lifelong mental health struggles. Amanda Clendenen, a 35-year-old professional photographer from Austin, said she sought guidance from a professional after seeing videos pop up on her TikTok “For You Page” about ADHD.

“All of a sudden, everything made sense [with] the things I thought were just weird quirks about myself,” she told CNN. “I took everything with a grain of salt, though, because I am not a professional, and neither are most of the people on TikTok, but I didn’t want to dismiss it, either.”

She has since been formally diagnosed with ADHD. In addition to therapy, she continues to use TikTok as a resource and community. “It’s nice to find other people who are going through the same thing.”

Laura Young, a 42-year-old mother who was also recently diagnosed with autism, agrees, noting she’s found a support system on social media. “TikTok and Instagram have really been the only place where I can hear from actual autistic people from around the world and hear their unfiltered experiences directly,” Young said.

Mitnaul of the Be Well Academy said that adults, in contrast to teens, are able to look at social media posts about mental health more objectively and create curiosity around something they’ve struggled with as a way to take better care of themselves.

“Teenagers are more likely to take in the information and use it as a diagnosis before consulting a professional or an adult who can help interpret what they’re seeing,” he said.

Coleman, whose daughter became obsessed with diagnosing herself online, said her teenager has improved thanks in part to abiding by limitations on social media, such as time constraints for Instagram and parental controls. Coleman has also downloaded apps to help monitor her daughter’s accounts.

“Although she’s been doing much better, she is still very heavily invested in reading up on diagnoses. She’s very into writing, and all of her characters have a diagnosis,” Coleman said. “This is such a vulnerable, impressionable age.”

Read the full article here