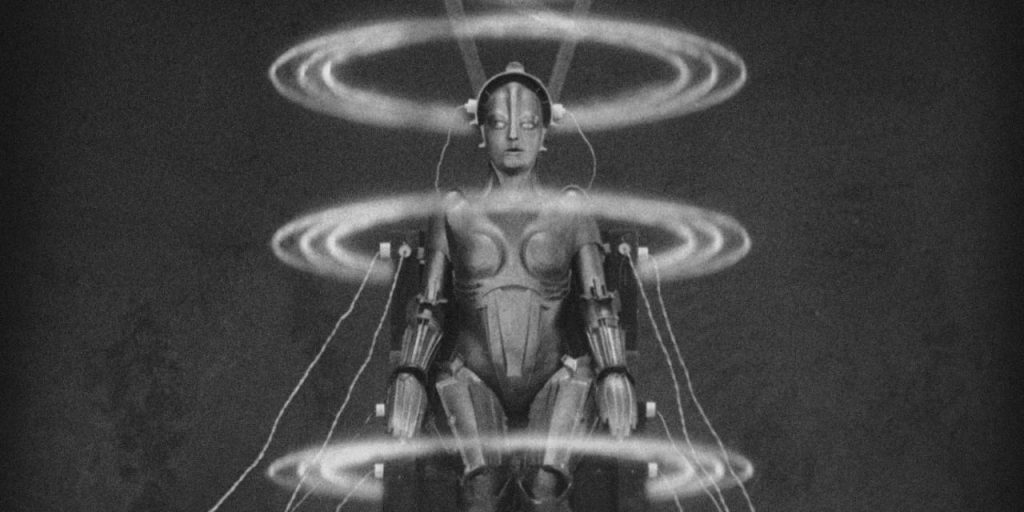

The rise of generative artificial intelligence heralds a new stage of the Industrial Revolution, one where machines think, learn, self-replicate, and can master many tasks that were once reserved for humans. This phase will be just as disruptive—and transformative—as the previous ones.

That AI technology will come for jobs is certain. The destruction and creation of jobs is a defining characteristic of the Industrial Revolution. Less certain is what kind of new jobs—and how many—will take their place.

Some scholars divide the Industrial Revolution into three stages: steam, which started around 1770; electricity, in 1870; and information in 1950. Think of the automobile industry replacing the horse-and-carriage trade in the first decades of the 20th century, or IT departments supplanting secretarial pools in recent decades.

In all of these cases, some people get left behind. The new jobs can be vastly different in nature, requiring novel skills and perhaps relocation, such as from farm to city in the first Industrial Revolution.

As shares of companies involved in the AI industry have soared, concerns about job security has grown. AI is finding its way into all aspects of life, from chatbots to surgery to battlefield drones. AI was at the center of this year’s highest-profile labor disputes, involving industries as disparate as Detroit car makers and Hollywood screenwriters. AI was on the agenda of the recent summit between President Joe Biden and Chinese President Xi Jinping.

The advances in AI technology are coming fast, with some predicting “singularity”—the theoretical point when machines evolve beyond human control—a few years away. If that’s true, job losses would be the least of worries.

“Mitigating the risk of extinction from AI should be a global priority alongside other societal-scale risks such as pandemics and nuclear war,” wrote a group of industry leaders, technologists, and academics this year in an open letter.

Assuming we survive, what can the past show us about how we will work with—or for—these machines in the future?

Consider the first Industrial Revolution, where mortals fashioned their own crude machines. Run on Britain’s inexpensive and abundant coal and manned by its cheap and abundant unskilled labor, steam engines powered trains, ships, and factories. The U.K. became a manufacturing powerhouse.

Not everyone welcomed the mechanical competition.

A “wanted” poster from January 1812, in Nottingham, England, offers a 200-pound reward for information about masked men who broke into a local workshop and “wantonly and feloniously broke and destroyed five stocking frames (mechanical knitting machines).”

The vandals were Luddites, textile artisans who waged a campaign of destruction against manufacturing between 1811 and 1817. They weren’t so much opposed to the machines as they were to a factory system that no longer valued their expertise.

Machine-breaking was an early form of job action, “collective bargaining by ‘riot’,” as historian Eric Hobsbawm put it. It was a precursor to many labor disputes to follow.

The second Industrial Revolution, kick-started by the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869, propelled the U.S. to global dominance. Breakthroughs including electricity, mass production, and the corporation transformed the world with marvels like cars, airplanes, refrigerators, and radios.

These advances also drew a backlash from people whose jobs were threatened.

“Only the lovers who flock to the dimmest nooks of the parks to hold hands and ‘spoon’ found no fault with the striking lamplighters last night,” the New-York Tribune wrote on April 26, 1907, after a walkout by the men who hand-lit the city’s 25,000 gas streetlights each night.

The lamplighters struck over claims of union busting, but the real enemy was in plain sight: the electric lightbulb.

“In the downtown part of Manhattan, where there are electric lights in plenty, there was no inconvenience,” the Tribune reported. The days of the lamplighters’ centuries-old trade were numbered.

Numbered also were the days of carriage makers, icemen, and elevator operators.

The third Industrial Revolution, meanwhile, rang the death knell for switchboard operators, newspaper typesetters, and most anyone whose job could be done by a computer.

Those lost jobs were replaced, in spades. The rise of personal computing and the internet led directly to the loss of 3.5 million U.S. jobs since 1980, according to McKinsey Global Institute in 2018. At the same time, new technologies created 19 million new jobs.

Looking ahead, MGI estimates technological advances might force as many as 375 million workers globally, out of 2.7 billion total, to switch occupations by 2030.

A survey conducted by LinkedIn for the World Economic Forum offers hints about where job growth might come from. Of the five fastest-growing job areas between 2018 and 2022, all but one involve people skills: sales and customer engagement; human resources and talent acquisition; marketing and communications; partnerships and alliances. The other: technology and IT. Even the robots will need their human handlers.

McKinsey Global’s Michael Chui suggests people won’t be replaced by technology in the future so much as they will partner more deeply with it.

“Almost all of us are cyborgs nowadays, in some sense,” he told Barron’s, pointing to the headphones he was wearing during a Zoom discussion.

In The Iliad, 28 centuries ago, Homer describes robotic “slaves” crafted by the god Hephaestus. Chui doesn’t expect humanoid robots, like Homer’s creations, to “come down and do everything” we once did.

“For most of us,” he says, “it’s parts of our jobs that machines will actually take over.”

Each wave of the Industrial Revolution brought greater prosperity—even if it wasn’t equally shared—advances in science and medicine, cheaper goods, and a more connected world. The AI wave might even do more.

“I’ve described it as giving us super powers, and I think it’s true,” Chui says.

Superpowers or extinction—starkly different visions for our brave, new AI future. Best hang on.

Write to [email protected]

Read the full article here