Russia’s withdrawal from the Black Sea Grain Initiative (BSGI), which allowed for agricultural exports from three ports in the Odesa region in south Ukraine, has also ended a broader arrangement that enabled both countries to continue exporting via the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov, despite the ongoing war in Ukraine.

Ukraine has responded by making credible threats to target any vessels heading towards Russian or Russian-occupied Ukrainian ports in the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov. The likely aim is to halt Russian Black Sea exports unless Russia returns to the grain agreement.

Since Aug. 1, 2022, when the BSGI became operational, Ukraine has exported 33 million tons of grain and sunflower seed, and oil via the grain corridor, representing nearly half of its total agricultural exports. (The other half was exported overland.)

Vessels most likely to be targeted by Ukraine are those directly associated with the Russian state or suspected of being involved in exporting grain from the Russian-occupied ports of Berdyansk or Mariupol in Ukraine, as well as any vessels suspected of breaching US or EU sanctions on Russia. The risk is highest to vessels anchored in the Black Sea waiting to pass through the Kerch Strait or underway towards the Kerch Strait, where they are most vulnerable to Ukrainian unmanned surface vessels (USVs).

Port Infrastructure at Berdyansk and Mariupol, but also the Russian ports of Azov, Rostov-on-Don, Taganrog, Yeysk, and Novorossiysk is now more likely to be targeted with long-range missiles and/or USVs.

Repeated Ukrainian strikes on the Kerch Strait Bridge are likely in the coming months, leading to temporary restrictions on navigation through the strait for up to one or two weeks at a time. In the event of a Ukrainian strike destroying the section of the Kerch Strait Bridge over the navigable channel, vessels would become trapped in the Sea of Azov for up to several weeks or even months if further strikes delay clearance work.

Russia rejoining the BSGI would be a ‘game changer’ event, reducing the risk to Ukrainian and Russian ports, and to the Kerch Strait Bridge.

MENA impact

Disruption to agricultural exports from Ukraine will heavily impact food import-dependent countries in the Middle East and North Africa region that are already experiencing domestic unrest and ongoing conflict, exacerbated by the loss of reexported flours from Turkey. S&P Global data show that Turkey was the fourth-largest wheat importer in the world in 2022, with most of its imports being refined and re-exported, making it the largest refined wheat exporter globally.

In MENA, Iraq, Syria, and Yemen would be most impacted by limits to Turkish refined wheat exports due to their respective severe political instability or conflict and are more reliant on international aid. Other than this, food price inflation raises the risk of related protests, especially in Iraq, Tunisia, and Lebanon. Yemen and Syria are particularly exposed as recipients of food aid from the World Food Programme (WFP). In 2023, 80% of WFP grain came from Ukraine, compared with approximately 50% before the war. The Syrian government is likely to be able to rely on its relationship with Russia to mitigate the broad impacts of grain shortages, although small protests over food inflation are likely.

Egypt, as the world’s largest importer of wheat, is also likely to be negatively impacted by the breakdown of the BSGI. Still, it is unlikely to experience significant social unrest as a result. The Egyptian government has diversified its total wheat imports since the start of the war in Ukraine, but the loss of access to Ukrainian exports and resultant higher prices are likely to further exacerbate inflation, which we expect to average 32.5% in 2023.

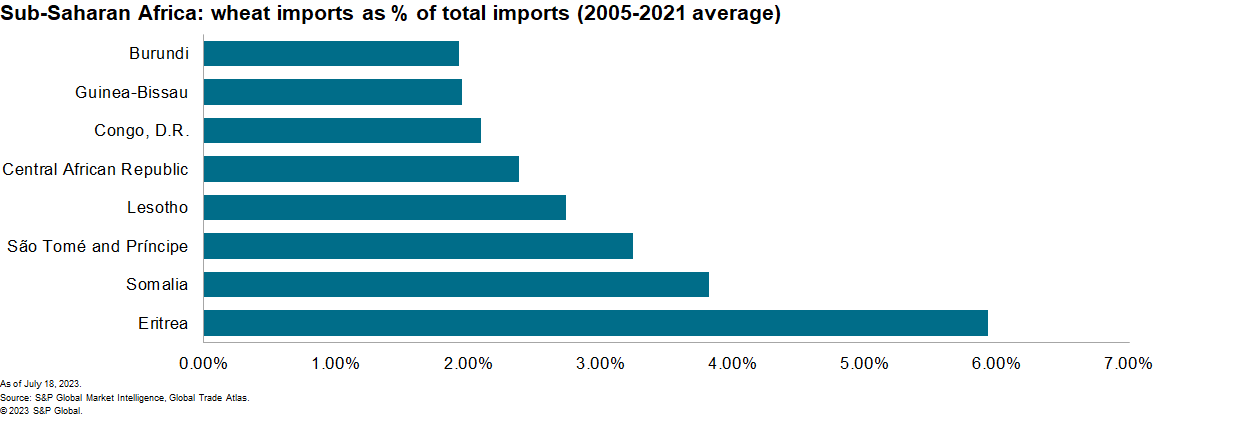

Sub-Saharan Africa impact

The suspension of the BSGI is likely to result in a sharp increase in food prices in several East African countries, which will in turn probably result in a significant reduction in humanitarian agencies’ supply of food to drought-affected areas and an escalation in social unrest. Sudan, which has been engaged in an internal conflict since April 15 between the armed forces and the country’s largest militia, is likely to be most affected by the suspension of BSGI, given that Russia and Ukraine provide 80% of Sudan’s wheat imports. This is likely to compound shortages of basic foodstuffs, which have already been created by the conflict, affecting availability in shops and aid agencies. Several East African countries are likely to be severely affected, given that the Horn of Africa region has been dealing with the most severe drought in almost fifty years.

Within sub-Saharan Africa more broadly, the likely secondary incremental effect on food prices due to the BSGI suspension will probably compound existing social vulnerabilities in South Africa, Angola, and Mozambique. This is likely to result in occasional incidents of protests and looting. For West Africa, the commencement of the rainy season, which makes local food produce widely available, is likely to mitigate imported food inflation, lowering the risk of social unrest.

S&P Global

APAC impact

A prolonged suspension would further encourage food-exporting Asia Pacific countries to prioritize domestic markets due to weather events and affected domestic production. According to UN data as of July 2023, Mainland China has been the largest recipient of food commodity exports facilitated via the BSGI since 2022 and continues to require wheat, corn, soybean, and rice imports. Mainland China, therefore, has a high incentive to encourage Russia to rejoin the BSGI, and through diplomatic efforts.

Such efforts are also likely by India. While the country produces sufficient rice, wheat, and dairy (among other food commodities) to meet domestic demand, a potentially erratic monsoon forecast – ongoing from July to September – is sharpening the government’s risk perception of food security, especially in a pre-election year ahead of India’s 2024 parliamentary vote. India’s Ministry of Consumer Affairs banned the export of non-basmati white rice with immediate effect on 20 July – more such export control policies are likely.

More broadly in the region, the likely onset of El Niño affecting India, Indonesia, Thailand, and Vietnam means that the BSGI notwithstanding, APAC countries exporting food commodities including rice, wheat, sugar, and palm oil will be more likely to prioritize domestic food security over exports in the second half of 2023, going into 2024. Therefore, should the suspension of BSGI be prolonged, the wider impact on the global food supply is likely to be exacerbated.

Original Post

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.

Read the full article here