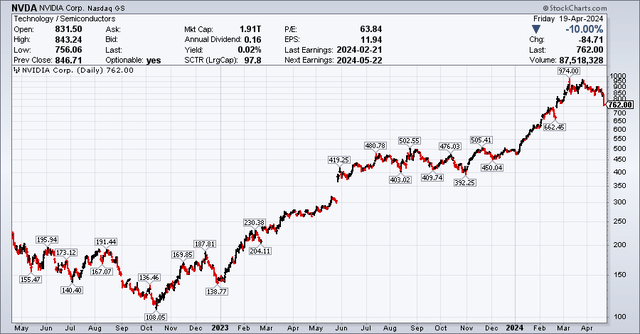

Nvidia Corporation’s (NASDAQ:NVDA) stock price has been on a tear since October 2022, rising from a low of $108/share to $974 in March 2024. Recently, the stock price has slid to $762, falling by 10% on Friday, April 19, 2024 (the market cap is still $1.9 trillion). Is it a buy or sell? I think its trajectory may mirror that of Tesla (TSLA) starting in 2021. I base this view not on artificial intelligence’s (AI) prospects, but because I believe markets are underestimating the incentive that Magnificent Seven have to develop alternatives and its impact on NVDA, in a nutshell: increased competition.

NVDA stock price (stockcharts.com)

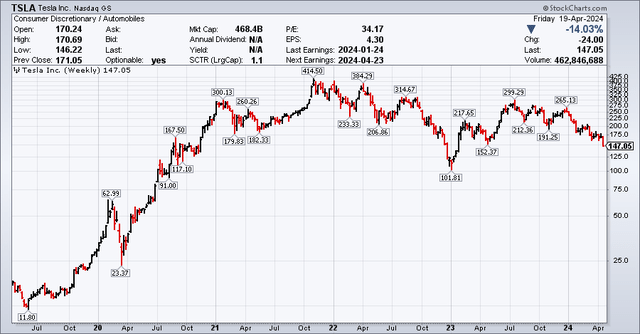

In 2021, Tesla seemed to be on a roll. From a low of $11.8/share, TSLA soared to $414/share by late 2021. Some analysts wondered if traditional auto companies could ever keep up with Tesla.

TSLA stock price (stockcharts.ccom)

But Tesla’s surge came to an abrupt halt as the “everything bubble” ended. Even now, TSLA is trading at $147/share, which is almost down to a third of its peak, while the Nasdaq (COMP.IND) and S&P 500 (SP500) are near record highs. What happened? The market underestimated how fast competition would arise to erode Tesla’s edge. Within a few years, competitors across the world (from China, South Korea, Europe, to the USA) were rolling out far too many models, and this has resulted in a surplus of electric vehicles (“EVs”). Now Tesla is reducing production and conducting layoffs amidst a sagging stock price.

I believe NVDA is headed for the same trajectory, mainly because NVDA sells towards enterprises, not consumers:

- Consumers can become captive

Many books and great investors describe how captive consumers are an important part of a profitable business model.

According to the book, “The Deals of Warren Buffett,” when Warren Buffett was young, he tried to start a new gas station where an existing incumbent already had a loyal following. Even though he tried very hard, he could not win customers from the next door gas station that was already well established. He lost several thousand dollars, learning the significance of customer captivity.

The book “Competition Demystified” delves into how captive customers and economies of scale are behind some of the most successful business models (the book gives Budweiser, etc., as examples).

Charlie Munger also mentioned how Wrigley can charge more for chewing gum because you’re putting something in your mouth, which is a pretty personal place, and you’re happy to pay a few extra cents for a product you know is ok.

This is essentially because consumers have a limited bandwidth to make decisions. There’s an opportunity cost for consumers to think about each decision (e.g., which type of Coke to buy or which cable service to subscribe to). Given the sheer volume of decisions consumers have to make daily, consumers have to prioritize their time. Eventually, decisions such as which type of soft drink to buy are simplified because it’s not worth dwelling on them, and time can be spent on far more important decisions (housing, education, healthcare, investments etc.) or leisure. Companies can then charge more because they know consumers are more likely to buy a certain product, rather than spend a lot of time comparing with competitors’ products and agonizing over each minor purchase.

This applies to tech stocks, too. Most of the Magnificent Seven (Microsoft, Apple, Meta, Alphabet, Amazon, Tesla, Nvidia) have business models where consumer or user captivity play important roles:

|

Company |

How Captivity Works |

|

Microsoft (MSFT) |

1. Network effects of everyone using the same software/cloud services 2. For most users, it is not worth the hassle to figure out how to use open-source alternatives compared to the several hundred dollars saved. 3. Even for corporate users, the cost of Microsoft’s services are peanuts compared to overall business revenues, so it’s an acceptable cost of doing business just to use Microsoft than figuring out alternatives. |

|

Apple (AAPL) |

1. Network effects from using same phone. 2. Consumers can use the same interface and don’t have to re-learn (e.g., if they first purchased an Apple phone and then purchased a Samsung phone) |

|

Meta Platforms (Facebook) (META) |

1. Network effects 2. Addictive scrolling of screen/feeds |

|

Google (Alphabet) (GOOGL) |

1. Network effects 2. As long as the search results are usually useful, users don’t want to hassle over whether google, Bing or others are better. |

|

Amazon (AMZN) |

1. Network effects as a platform 2. As long as prices are reasonably competitive, users don’t want to agonize over whether to use Amazon or some new shiny app (unless prices are much lower, like Temu) |

Given limited time and resources, consumers opt for shortcuts and just use a trusted brand, as long as the cost (as percentage of total spend) is reasonable, and the markup is not too egregious. It is not difficult to see this going on every day, just watch how long a teenager can spend on social media with his/her eyes glued to the screen. Imagine what Facebook’s business model would be if users did not spend an average of 30 minutes on the platform each day, scrolling through feeds etc.

2. While corporations control exposure and reliance on vendors

But this is NOT how corporations work. And NVDA’s sales are mostly from corporations. In fact, 40% of its recent sales may be from four customers (Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, Meta). The mindset of corporate procurement personnel making the decisions to procure NVDA chips is vastly different from YouTube viewers clicking on the next suggested video.

Some of the most successful corporations in the world can at least partly attribute their success to rigidly managing their supply chain and cost, e.g., Apple. A corporation cannot become solely dependent on one supplier for key, critical parts that comprise a large portion of their costs; otherwise the risks are too large.

For example, there is little competition with ASML Holding (ASML) to make the world’s advanced chip-making lithographic machines because at the end of the day, it’s a tiny portion of the overall semiconductor value chain. Though it has a market cap of 325 billion Euros, ASML cannot easily extend into application fields (i.e., it cannot build the chips as it is not a fab, and it cannot create an Amazon or Google just based on its EUV machines). When your supplier has a fraction of your market cap and revenue and cannot easily extend into your turf, then said supplier receives a pat on the back and a “Supplier of the Year” award.

But when Nvidia stock has a market cap of $2 trillion (rivaling the Magnificent Seven) and many of the Magnificent Seven are spending billions of dollars annually on NVDA products, then this raises eyebrows:

- Demand outstripping capacity: if NVDA is unable to fully meet the demand, this could curtail a business’s AI plan and strategy.

- Concentration risk: It is hard for companies to justify to their boards how they can spend many billions of dollars a year on NVDA chips and not have a back-up plan. Boards will ask what’s their plan B for if NVDA cannot meet demand or does not supply them and they will have to come up with a plan B. The CEO has to do something, if even just to tell the board he’s addressing the risk.

- NVDA’s $2 trillion market cap helps competitors justify internally developing AI chips: Companies need to justify new initiatives to their CEOs and boards, which need to balance costs, capital outlays, potential profits, as well dilution of Management attention. Given the overall economic uncertainties, this is not easy (note how Apple cancelled its car project and META has reduced investments in Metaverse). If NVDA’s market cap was a few hundred billion dollars, then it might be harder to justify taking action. But when it’s $2 trillion, then it’s not just a rosy internal forecast on an Excel spreadsheet made by corporate managers pushing for an internal project, but what the market estimates this technology is worth (at least for now). Then it’s much easier for companies to persuade all internal stakeholders that it’s worth developing AI chips to reduce NVDA’s bargaining power (if not cut it out altogether) and capture the profit margins/reduced costs for themselves.

- This is not a farfetched theoretical scenario. Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, and Meta are all reportedly working on in-house AI chips. NVDA might be ahead, but can it outcompete four other determined behemoths?

Risks to bearish thesis:

On the flip side, it is also possible that NVDA can continue to sustain or even grow its market cap if the rosy forecasts for AI chips are to be believed. Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, etc., may find developing AI chips to be more difficult than anticipated and give up (e.g., Apple’s recent cancellation of its car project). Many market observers have been bearish on tech stocks in the past decade, while tech stocks kept powering ahead. So while I am bearish from the perspective of business model (i.e., sales mainly to corporate customers) and competitive dynamics, it is definitely possible that NVDA could overcome all of this and defy these bearish doubts.

Conclusion:

As the old saying goes, “sell to the masses, live with the classes, sell to the classes, live with the masses.” In my opinion, there is no tech company that is worth trillions based off tech alone (rather, it is more based off captive users that watch one YouTube video after another), hence most of the Magnificent Seven have become Magnificent by selling to the mass market (not selling to other big tech corporations).

Unfortunately, in this sense, NVDA may ultimately be a victim of its own success (or rather, parabolic stock price rise). It may have overlooked that corporations work differently from consumers: by providing competitors with internal justifications (hey it’s worth $2 trillion), rosy forecasts (trillions of dollars needed to develop general purpose AI), its customers today are rushing to develop alternatives (e.g., internally or by funding Intel, AMD, etc.) and I think this may severely diminish NVDA’s long-term prospects.

Therefore, I see a long-term market cap for NVDA at levels significantly lower than today’s $1.9 trillion as at April 19, 2024, and have a bearish rating NVDA unless it can demonstrate it is so irreplaceable other companies are unable to develop economically feasible alternatives. I would not suggest individual investors to go short NVDA either, as the past track record of TSLA and NVDA indicate this could be quite risky as valuations could continue to increase with no end in sight. However, investors that are investing money they cannot afford to lose (e.g., significant amounts of retirement savings) should be cautious with NVDA, or at least consider keeping risk exposure to a manageable level.

Read the full article here